SOS Canadian Coast Guard and Search & Rescue was needed (Part 1)

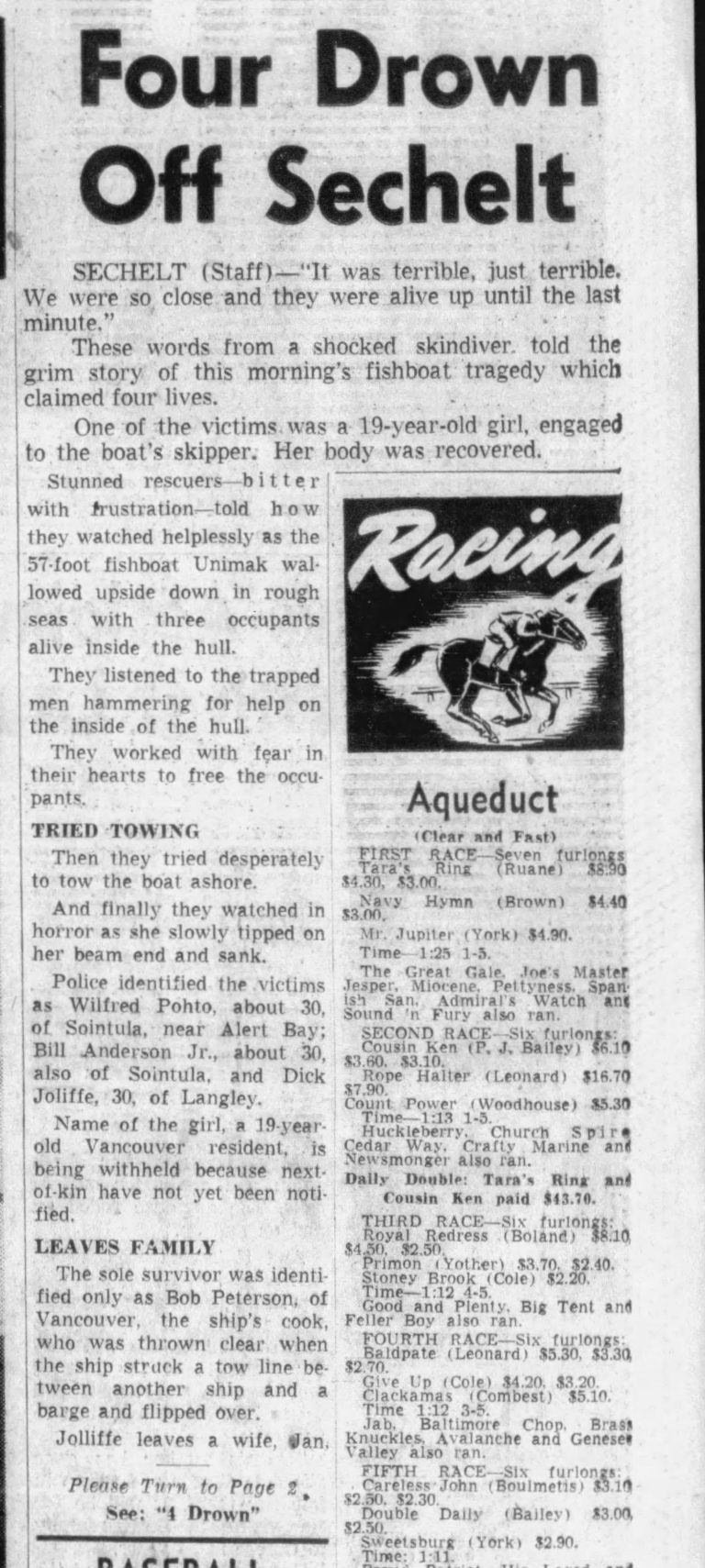

In the early morning darkness of July 23, 1960, off British Columbia’s Sechelt coast, the fishing boat Unimak struck a tow line pulling a barge. Within no time other fishing boats responded to the Unimak listening to crew trapped in the haul. They tapped to those outside hoping they would be saved. But by who? Sadly, in 1960 there was no dedicated search and rescue crews of the type we know today. The men died when their boat finally sunk in 70 fathoms of ocean. Four people in total were drowned that night, only one crew member survived. What happened on those dark waters would shake up the government of John Diefenbaker and the Department of Transport. Sadly, this sinking was the second shipping disaster on the west coast in a little over a year. Thankfully it led the nation to the realization that a Canadian Coast guard was needed, and it had to have a Search and Rescue fleet.

Ferngulf Freighter Explosion

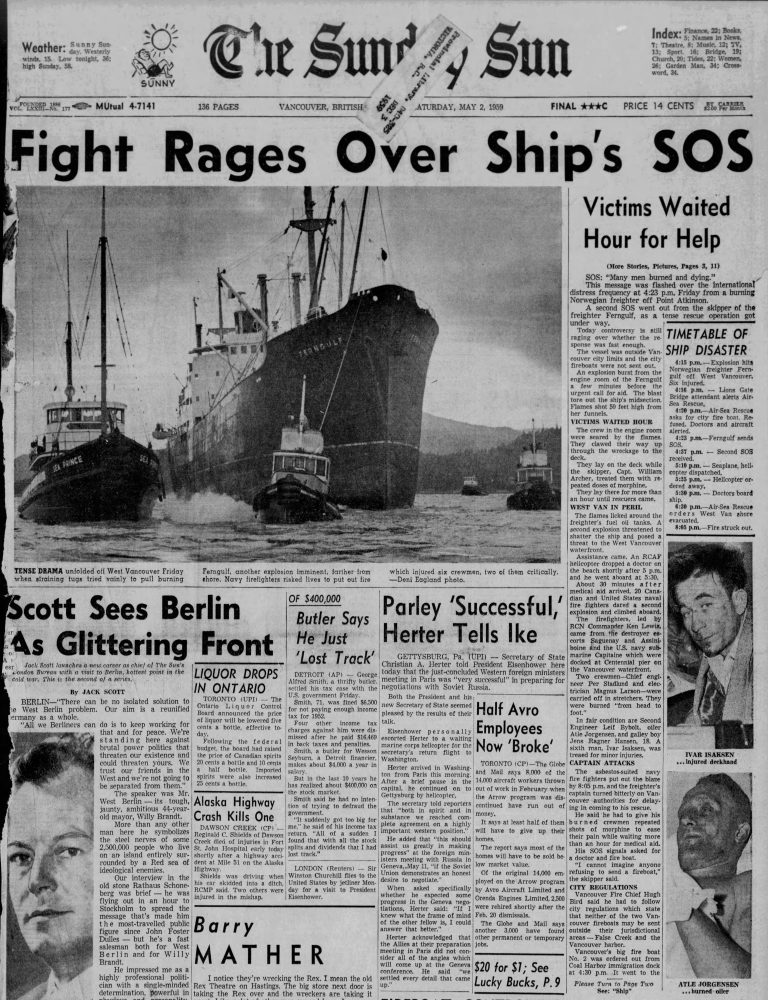

SOS: Many men burned and dying was the message flashed over the international distress frequency at 4:23 pm on Friday May 1, 1959. The call was from the burning Norwegian freighter Ferngulf off Point Atkinson, within sight of Vancouver. The crew was just sitting down to their evening meal when an explosion erupted under their feet. There was a deafening roar and sheets of flames. The saloon tables sagged and crashed, and the bulkheads caved in.

Within minutes, the Vancouver fire alarm operator informed the Fire Chief there had been an explosion on a boat and several injuries. The skipper was asking that a fire boat be dispatched, and a doctor sent to the ship. The Air-Sea Rescue Co-ordinator called stating that a Norwegian freighter four miles west of First Narrows bridge had suffered an explosion out of its funnel and its master had requested first aid help and a fire boat. But without a Coast Guard to coordinate the rescue, confusion took hold. The Fire Chief could not take any action without the approval of the Mayor of Vancouver. The mayor was out of the office. The chief then turned to the City Commissioner who was worried about sending out the fire boat because it would mean leaving the harbor unprotected. Furthermore, City Council had passed an earlier resolution that the fire boat should not leave city limits, so he felt he didn’t have the authority. The Ferngulf was within sight of Vancouver but not within the city limits, it was on fire but beyond help it seemed.

Foam, hoses, and nozzles were transferred to a Royal Canadian Air Force crash boat which was meant to rescue aircrew in the case of an Airforce airplane going down in the ocean. Fire boat No. 2 was ordered to standby in case the freighter was towed into the Burrard drydock where only then could it fight the fire. In the days that followed no one could supply concise information as to the extent of the poor response. Dispatching of medical aid was being handled by the Department of Transport (DOT) Marine-Sea rescue service. Many small boats responded to the SOS and were around the freighter to help with evacuation. But there was no real coordination. Fortunately, there were two Royal Canadian Navy destroyers in port, the Saguenay and the Assiniboine. Their commander ordered the fire crews from both ships to respond, and they succeeded in bringing the fire under control after 4 hours.

The explosion was probably caused by “an overheated thrust bearing igniting fuel vapor in the crankpit” the coroner’s inquiry was told. A survivor, 18-year-old Cabin Boy Jen Hansen, said “I was reading The Sun in my bunk and then came – the explosion. The engine room. It’s underneath me. I think it was oil burner. There was all smoke. I couldn’t see anything. I don’t remember what happened. I was standing by the window – only there wasn’t any. There wasn’t any window. There weren’t any walls. The smoke cleared. There were no walls anymore. I walked out on deck. My feet hurt.”

The Ferngulf Chief Engineer, Per Stadlund, was burned from head to toe, The lower part of his body and limbs were without skin, but his first thoughts were for his ship and the crew. He pulled himself up to the controls and brought the ship to a halt, ending the danger of grounding or a collision. “I sent an SOS and ran down here to see if there was anything I could do,” said Captain Willian Archer. He opened a door and stepped into space. Only by grabbing at a tiny railing at his side did he saved himself from plunging into the inferno below. “I don’t know yet how they got out of there with the platform gone,” he said.

The following day the captain angerly attacked Vancouver authorities for failing to answer his distress call. “I sent an SOS as soon as the explosion occurred, and we were told by the city we were outside limits. Then, more than an hour later, we were told a fireboat and a doctor were coming. We never saw a fireboat, and a helicopter which came, circled but did not land. We had no doctor aboard, and so for an hour the men had no treatment except from me. I kept shoving morphine into them” Capt. Archer told local media. Finally, an Air Force doctor and Corporal was brought by helicopter from Sea Island. While there was confusion with the rescue efforts the danger was realized on land and the North Vancouver Police were organized enough to go door to door removing 50 families along the shoreline for fear another explosion would endanger people facing Burrard Inlet. The concern was real given the fire was getting close to the ships 400 tons of fuel oil.

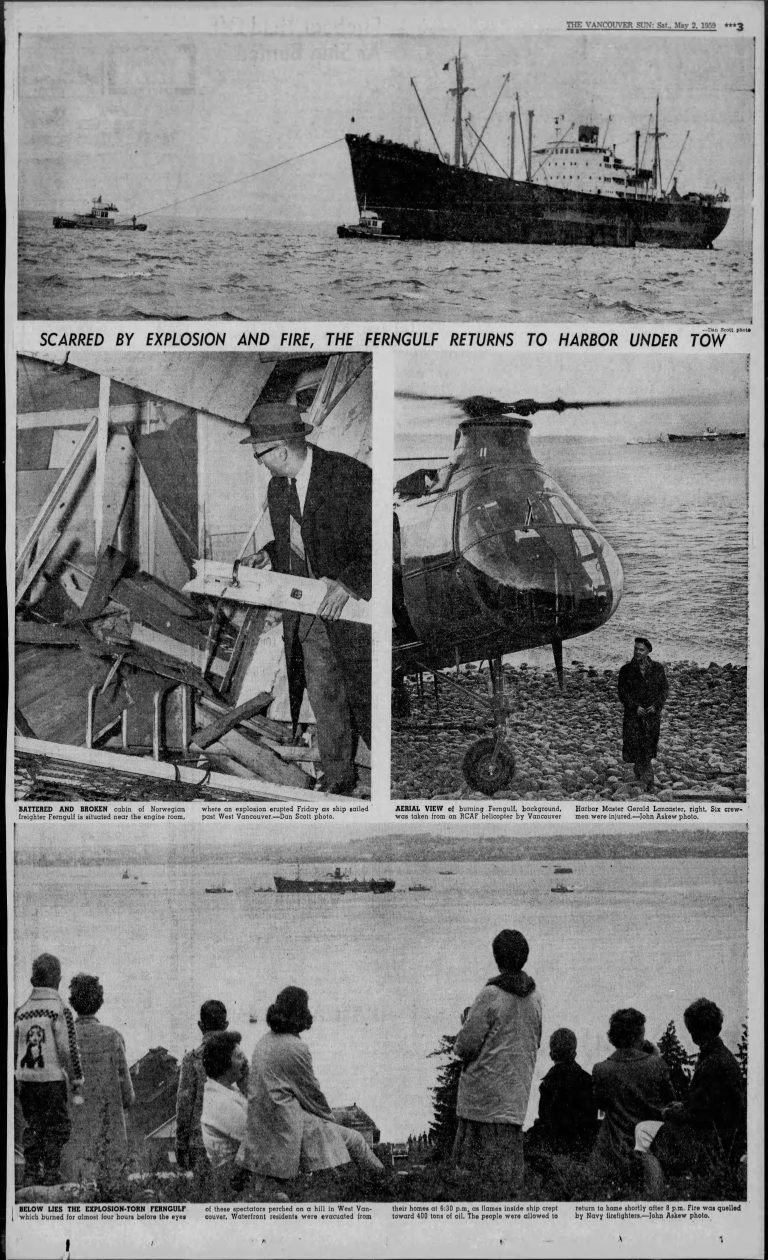

On May 2nd the Ferngulf “limped back to the Burrard shipyards” a dead ship, dragging aimlessly in tow of a bevy of harbor tugs. They couldn’t turn the Norwegian flag upside down as a distress signal because it looks the same both ways, so the tow crew added a Canadian ensign on a foremast that “fluttered idly in the light wind, union down.” The international distress symbol spoke not only to the ship but Canada’s response to disasters at sea. The lack of response was quickly gaining international attention. A Norwegian newspaper branded Vancouver’s refusal to send aid to the burning freighter “approaching a criminal act.” The ships owners told the paper “I doubt we can do anything more than condemn morally a red-tape mentality like this.”

As the debate on the failed response went on, the Chief Engineer, Per Stanslund, lay in the emergency ward with burns to 80% of his body. Fellow crewmate, Magnus Larsen, had already died in North Vancouver General Hospital. Stadlund, died in hospital on May 14th.

Sailors and the Canadian public were left to wonder just who was responsible for the rescue of those at sea in distress.