As part of UCTE’s continued exploration of its history, comes part 1 of a a3-part story about our first strike

In 1967, after decades of lobbying and agitation by the staff associations, Parliament passed Bill-170, the Public Service Staff Relations Act, which finally gave federal employees the right to unionize and to strike if they wanted. No more going cap in hand to request improvement in wages and benefits but instead the power to demand was now in the hands of federal public employees.

Federal employees were quick to sign union cards and in September of 1967, the Public Service Alliance of Canada gave notice to bargain for the Heating and Power (HP) and Firefighter (FR) members. The first ever PSAC collective agreements were for these two bargaining units, signed in April of 1968. The new union only formed in 1966 was off to a fast start.

By 1968 the PSAC was the bargaining unit for 53 groups. Of those only 8 were on the conciliation/strike route. Despite that the membership made it clear in those early days that they were going to take their fate into their own hands. The first strike in the history of the PSAC was a wildcat in the spring of 1970 by customs officers at the Windsor-Detroit crossing. The following year the Union of National Defence Employees took the first legal strike against Defence Construction at two locations. Then in the early 1970 members of the Union of Canadian Transportation Employees started taking job actions by holding wildcat strikes.

Part 3: All labour disputes must come to an end … so did the firefighters “study sessions”

Three weeks into firefighters’ walkout in April 1974, 3 small BC airports reopened: Terrace, Prince Rupert, and Abbotsford. Two days later, the firefighters in Vancouver returned ending the 18-day strike. The federal government agreed to the firefighters’ demands that a mediator be named. Tom O’Conner, a Labour Relations consultant, was to meet both sides in Ottawa.

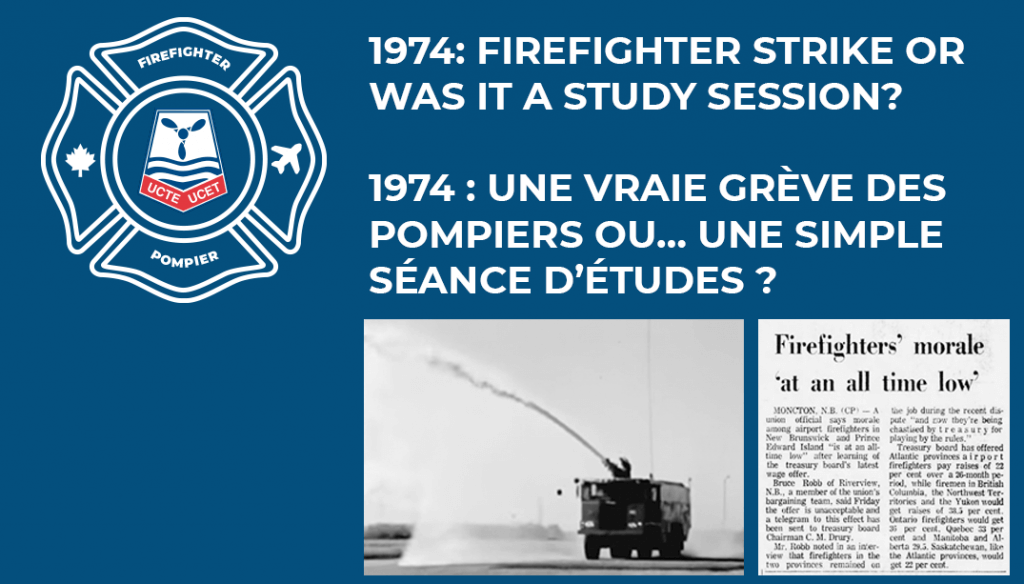

A few weeks later a new offer was presented. It had gone from 30 per cent across the nation to offering Atlantic province airport firefighters pay raises of 22 per cent over a 26-month period while those in British Columbia, the Northwest Territories and the Yukon would get raises of 38.5 per cent. Ontario firefighters would get 36 per cent, Quebec 33 per cent and Manitoba and Alberta 29.5 per cent. Saskatchewan, like the Atlantic provinces, would get 22 per cent. The original national demand had been for 44.5 per cent over two years. The Vancouver Firefighters indicated they were prepared to accept the Treasury Board’s proposed wage increases if they were in an 18-month contract rather than in the proposed 26-month agreement.

Vancouver’s local president, Don Duthie, told the media that, “most of the members I have spoken to seem quite pleased with it.” Bob Crowley, another Vancouver spokesperson for the firefighters, however admitted “he did not believe firefighters in the Maritimes, would be too happy with the latest offer.” And he was right! Local union representatives in New Brunswick and PEI said morale at airports was at an “all time low” because of the offer. Bruce Robb, a National Defence firefighter and member of the bargaining team, called the government offer unacceptable.

With the highest paid firefighters in the country in the City of Vancouver, and neighbouring municipalities, it was only natural that UCTE members in BC would want parity. However, airport firefighters in Newfoundland said parity “would be disastrous for us” since municipal firefighters in St. John’s made about $1,000 less per year.

There was no agreement in neither the membership nor between the parties. The federal government then placed the question of a settlement into binding arbitration. The arbitrator handed down a report in June awarding a one-year contract that raised wages to $11,262 from $9,160. Bill Brown, from the Vancouver local, said the increases of 22.9 per cent for men with more than five years’ experience and 19 per cent for all others was essentially what had been offered by the government and rejected. He said the members were unhappy and were considering decertification from the PSAC. The walkouts initiated by British Columbia locals began when members that were unhappy with a tentative agreement which offered total raises of 30 per cent over a 26-month contract, now were receiving an award that was much lower.

A question of solidarity

From the start of the struggle, it was clear that there was a division in the union on national rates vs regional rates of pay. The 1969 UCTE Convention had called for national rates as a component policy. The Alliance, at its 1973 national convention, had adopted a policy to bargain for national parity across the country. It’s important to note that bargaining regional rates was not only a PSAC-UCTE issue. The Canadian Labour Congress convention had overwhelmingly supported a Letter Carriers’ union motion that read; “Equal pay for equal work regardless of age, sex, race, creed, color, national origin, political and religious affiliations and location is the only logical way to equalize the standard of living of workers.”

Alliance leadership held a meeting with BC members following the strike and faced much criticism. PSAC President Claude Edwards, took the position that the federal Treasury Board wanted regional pay scales because it would save the government money. The membership was not happy with the increase but there was no agreement that regional rates were acceptable.

At the end of that one-year arbitrated collective agreement, in May of 1975 a new arbitrator gave the members a further 29 per cent increase over a new two-year agreement. Wages would increase to $13,177 from $11,262. The question of regional rates of pay would come up again in the 1990s as the federal government turned airports over to local authorities and the UCTE members began negotiating collective agreements with each airport.

At a time when most unions in the country called for national rates of pay and where, in the case of the UCTE Maritime firefighters, they feared regional rates would have meant much lower wages, the BC members had an uphill struggle to win their demands. The Vancouver local looked like they were supporting the employer’s position, which is never a good place to be during bargaining. But it was clear that the FR members across the country were unhappy with their wages and were willing to act by holding a wildcat strike. This action was in defiance of the law, the courts, the employer, and their union. But in the spring of 1974, the UCTE firefighters in BC lead the country into a “study session” that involved not going to work for 18 days.