National Day of Remembrance and Action on Violence Against Women

In collaboration with Denise Reynolds, UCTE Human Rights Officer.

In the late afternoon of December 6, 1989, a gunman arrived at the École Polytechnique in Montréal armed with a semi-automatic assault rifle and hatred in his heart.

The 25-year-old made his way into a classroom where he separated the men from the women and ordered the men out. Alone with the remaining nine female students, he declared his hatred for feminists before spraying them with bullets, killing six of them instantly. The others, wounded, played dead until he left the room.

He then moved methodically through the halls and cafeteria of the Université de Montréal’s engineering school, shooting more women, cutting some down as they ran for their lives, until he came to a second-floor classroom where he killed more as he ranted. After stabbing his final victim, he turned his gun on himself.

By the time police intervened, it was too late. The 20-minute rampage left 14 women dead, including 13 students and an administrative assistant.

The shooter targeted women who were destined for a non-traditional occupation, claiming that they were taking over from men.[1] It took decades to call it what it was; Canada’s first mass femicide.

In Canada, a woman or girl is killed every 2.5 days, yet there is widespread unwillingness to call violence against women what it is: an act of hatred. Though statistics on the rates of reported violence against women in intimate relationships show a decline over the last few decades, the reality is that violence against women has not been abated. Half of all women in Canada have experienced physical or sexual violence. Often the social and psychological costs of reporting gendered violence offer little recourse to justice. Then there is trying to get authorities to act. An investigative series in The Globe and Mail even found that over a period of 20 months, 1 out of every 5 women who reported being assaulted had their cases dismissed by police as “unfounded.” If we are to play a role in eradicating this epidemic, we must provide a better, more consistent, and nuanced approach in our support of any woman, transgender, or non-binary person who has experienced violence, abuse, or harassment.

Recently heightened media attention on some high-profile cases has galvanized the public’s glare and gaze on these violations of human dignity. The #MeToo and #BeenRapedNeverReported are examples of movements that have successfully raised public awareness.

Tougher gun control restrictions have been introduced in Canada, due in part to the important work of several Polytechnique survivors who continue to press for tighter restrictions to this day.

Emergency responders receive training on how to confront active shooters—how to manage their stress and emotions in the moment—in order to make the right decisions in dangerous situations.

This year, the federal government finally announced that it will ratify the International Labour Organization Convention no. 190 (C-190) on Violence and Harassment. According to the CLC, the ILO’s convention is a ground-breaking international agreement that acknowledges the universal right to a world of work free from violence and harassment, makes governments accountable for preventing and addressing this violence and harassment, and establishes a clear framework for achieving this.[2]

We remember December 6th as a Day of Action on Violence Against Women.

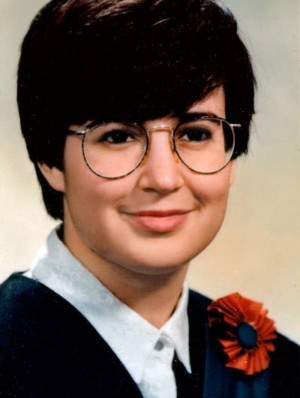

We remember[3]:

We remember these faces.

These lives lost to violence.

Targeted because they were women.

[1] https://theconversation.com/the-montreal-massacre-is-finally-recognized-as-an-anti-feminist-attack-128450

[2] https://canadianlabour.ca/progress-towards-a-world-of-work-free-of-violence-and-harassment/

[3] https://montrealgazette.com/news/local-news/remembering-the-polytechnique-victims