National Aviation Day: 1978 – The Cranbrook, B.C. Plane Crash: What Really Happened?

In 1978, on February 11, Pacific Western Airlines Flight 314, a Boeing 737-200, crashed at Cranbrook International Airport in British Columbia. The tragedy claimed the lives of 42 of the 49 people aboard.

In 1978 the Cranbrook Airport was considered an uncontrolled airport, as the traffic load was very low. It did not have an air traffic controller. Only a radio operator on site whose job was to give out information to pilots and to control vehicles on the ground.

Copyrights: Admiral_Cloudberg

Details of the Crash

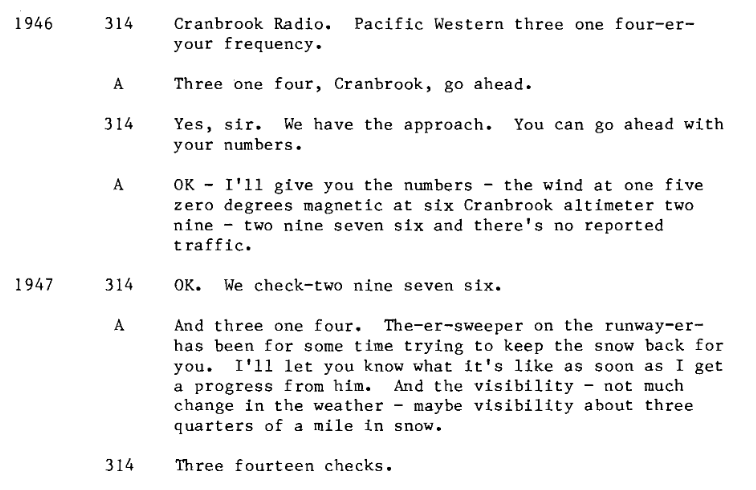

It all started at Calgary Airport. Visibility was reduced due to a snowstorm. At the beginning of the flight, communications between the pilots and the Cranbrook Airport confirmed that the plane would land at 1:05 p.m.

On the morning of the crash, nearly a metre of snow had already fallen in Cranbrook, and the storm was not over. Minutes before the arrival of the Calgary flight, the radio operator sent snowplow driver, Terry George, an UCTE member at the time, to clear the runway.

Captain Chris Miles, the 30-year-old experienced pilot who had been flying since the age of 19, received a communication about the snowstorm at Cranbrook. The visibility was 1.2 kilometres with falling snow. The radio operator had also indicated that a snowplow was clearing the runway, and 25-year-old First Officer, Peter Van Oort, a new recruit with 82 hours on the 737, responded, “Three fourteen checks[1]”, confirming the communication.

Copyright: Admiral_Cloudberg

These were the last communications between the Flight 314 crew and Cranbrook Airport.

Approaching the Skookumchuck beacon from the east, the pilots turned left to lock in the ILS signal for a straight-in landing. It was customary for pilots approaching Cranbrook to check in with the radio operator as they passed over the Skookumchuck beacon but, for some reason, the crew of Flight 314 did not.[2]

Some suppositions were made: the pilot and the first officer forgot to indicate the position of the aircraft. Arriving ten minutes early at the airstrip, UCTE member Terry George and his snowplow were still clearing snow.

At 12:55 p.m. on February 11, 1978, upon landing, the pilots did not see the snowplow. Terry was about 300 metres from the plane, which had landed. It was while trying to avoid the snowplow that Captain Miles called for a go-around. He overrode the reverse thrust control, slammed the throttles to full power, and backed up to climb.

Miles and Van Oort had pushed the throttles together with so much force that Miles broke his thumb.[3]

They managed to avoid Terry George on his snowplow. Due to mechanical problems triggered by the emergency measures, the pilots could not climb again. They began to lose speed and the plane became difficult to fly. The plane tilted 90 degrees to the left at an altitude of 400 feet. Flight 314 crashed on its left side into a snow-covered field, bursting its fuel tanks.

In the back of the plane, flight attendant Gail Dunn was stunned to discover that she had survived the crash virtually unscathed, as was a young man in the back row who rushed to help her open the emergency exit door. Both survivors stumbled out of the burning plane and into knee-deep snow. Just outside the plane, they managed to find an 11-year-old girl in the snow, injured but alive[4].

After the Crash

Terry George and the two airport firefighters all UCTE members at the time jumped into their emergency vehicle and rushed to the crash site. They found six survivors, almost all of them were in the last four rows of the plane.

The Cranbrook Airport is dependent on cities of Cranbrook and Kimberly department to assist. The airport. It took 25 minutes for those firefighters to arrive. By the time they reached the scene, the fire had consumed most of the plane and heroic airport employees had managed to extract as many survivors as possible.[5]

Eleven days after this tragic plane crash, another passenger died in hospital, bringing the final death toll to 43. Six survived.

Who is to Blame?

Soon after, Transport Canada opened an investigation. Almost all evidence was destroyed in the fires. Many tried to put the blame on the snowplow operator, Terry George, a member of UCTE. Yvon Demers, UCTE National Executive Secretary at the time, defended him, revealing communications showing Terry was in fact one of the heroes of the story. The final report showed the three responsible were Transport Canada, the pilots, and Boeing.

What must be understood is that errors were made in two steps:

- Communication problems concerning the snowplow

- Mechanical and human error contributing to the loss of control of the plane

At the time, Transport Canada had no safety rules in place regarding estimated times of arrival in dangerous conditions such as the one at Cranbrook. The pilots did not communicate their approach to the radio operator. However, regulations did not specifically require this communication. Flying conditions were poor.

The position of the radio operator was hardly referred to in the Canadian Air Traffic Control Regulations. Radio operators had no clearly defined duties, resulting in considerable variation in the level of interaction pilots could have with operators at a variety of uncontrolled airports.[6]

As for Boeing’s part, in 1977, the company updated the relevant section of its 737 flight manual to read, “Do not attempt a go-around after reverse thrust has been initiated.” This is exactly what occurred with the 737 flight and in several other incidents.

Ultimately, Transport Canada could not fault the pilots for attempting an unsafe procedure in such a situation.

“[But] given that the aircraft was intended to be used at smaller, ‘uncontrolled’ airports, the FAA standards must be considered inadequate or ill-defined.[7]”

The pilots of this aircraft did not have a chance. Safety measures were inadequate at the time, in addition to the mechanical change Boeing had instituted, and weather conditions. Pilots were faced with an impossible workload for 20 seconds, culminating in a nightmare scenario. Today, several safety measures are in place to ensure that this type of accident does not reoccur. Forty-three people died as a result of this crash which has forever marked the community of Cranbrook and members involved.

[1] https://admiralcloudberg.medium.com/margin-of-error-the-crash-of-pacific-western-airlines-flight-314-748a093102ba

[2] https://admiralcloudberg.medium.com/margin-of-error-the-crash-of-pacific-western-airlines-flight-314-748a093102ba

[3] https://admiralcloudberg.medium.com/margin-of-error-the-crash-of-pacific-western-airlines-flight-314-748a093102ba

[4] https://admiralcloudberg.medium.com/margin-of-error-the-crash-of-pacific-western-airlines-flight-314-748a093102ba

[5] https://admiralcloudberg.medium.com/margin-of-error-the-crash-of-pacific-western-airlines-flight-314-748a093102ba

[6] https://admiralcloudberg.medium.com/margin-of-error-the-crash-of-pacific-western-airlines-flight-314-748a093102ba

[7] https://admiralcloudberg.medium.com/margin-of-error-the-crash-of-pacific-western-airlines-flight-314-748a093102ba