Lack of Coast Guard Blamed for Tragedy in Fishing Boat Sinking (Part 3)

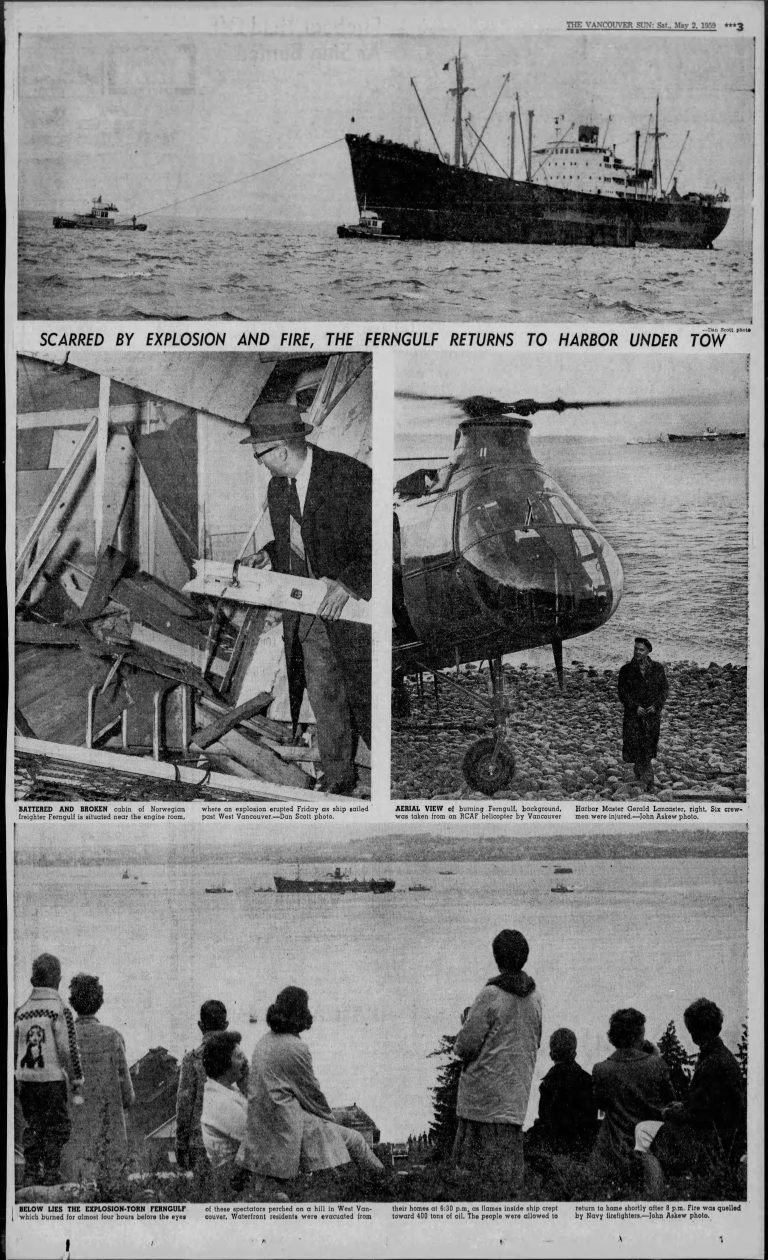

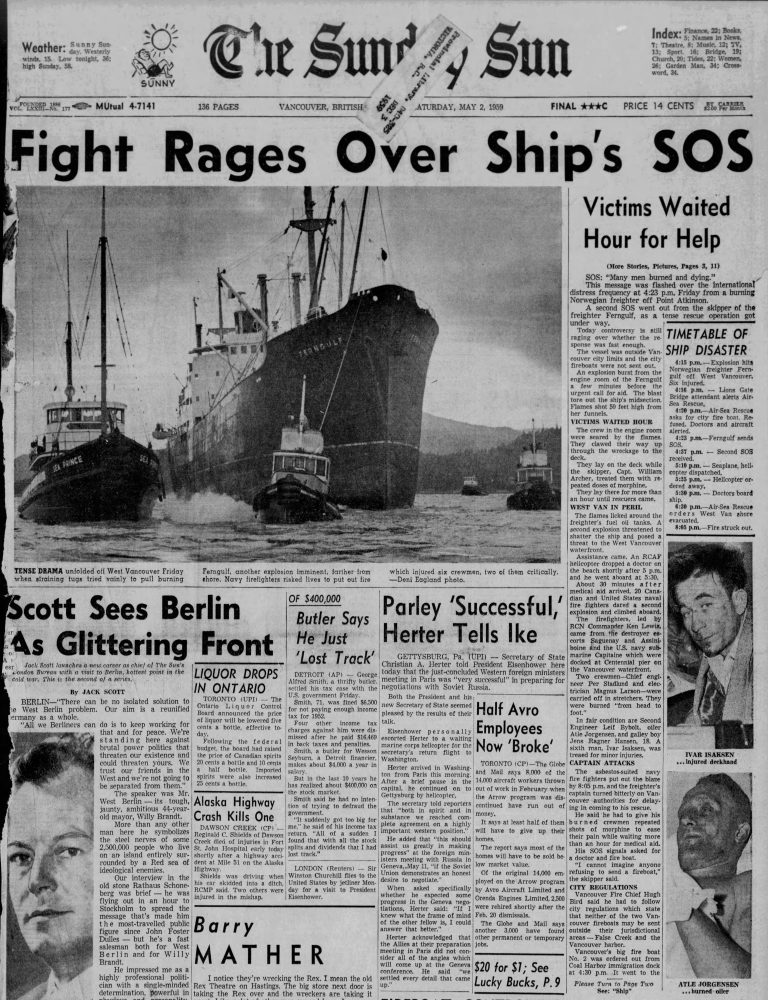

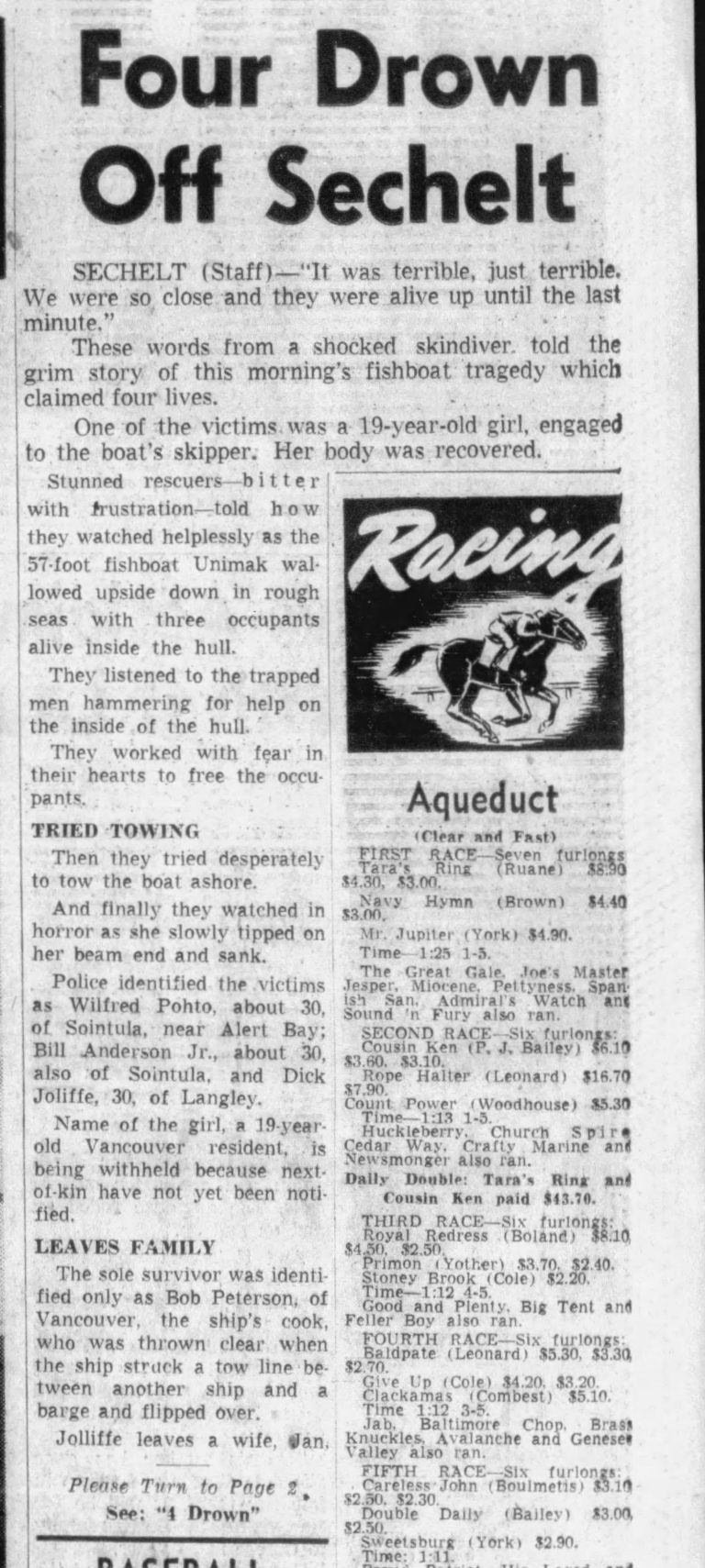

It was in the early hours of July 23, 1960, just a year after the Ferngulf explosion and another vessel needed a Coast Guard. The fishing boat Unimak had struck a barge towline in sight of Roberts Creek, off the BC’s Sechelt coast. The lives of the crew were immediately in danger. It took only minutes for the Unimak to capsize but for hours, two fishermen trapped in the hull of the upturned boat banged on the hull. Other fishing boats responded to the Unimak. They could hear the trapped men tapping, hoping someone would come to save them. But the would-be rescuers were helpless. There were many vessels around the fishing boat that night but no one to direct the rescue.

“It was terrible, just terrible. We were so close, and they were alive up until the last minute.” Those words came from one of those trying to save the men that night. There were two volunteers that donned their personal diving gear and entered the water and the upside-down craft. The loan survivor, Robert Pederson, 30, ship’s cook who was able to scramble to safety drew maps and guided the divers to the area the knocking was coming from. They recovered one body but a jammed door to the engine room prevented them from gaining access to the trapped men. The divers were under water in the wheelhouse when the boat shifted and started losing air forcing them to give up their rescue attempt.

13 boats surrounded the capsized vessel that night. Capt. Angus Campbell of the Canadian Pacific Ship Princess of Vancouver was eight miles from the accident scene when he responded to the call for help. He positioned his ship to function as a breakwater and provided lighting for those attempting the rescue. When the crash boat arrived on the scene, they had to send ashore for rescue tools they did not have. The Department of Transport (DOT) four-man dive team were given the wrong location of the boat. When they finally arrived 30 minutes before the boat sank, they deemed the sea too rough to enter the boat. One of the rescue boats had secured lines to the Unimak and its crew had to be evacuated when its booms, mast, and rigging all collapsed under the weight, threating to sink their craft as well.

Of the 5 on board, one loan survivor, the ship’s cook, was pulled from the water by the first boats that arrived. Joan Hornell, a guest on board, was found in the wheelhouse by the volunteer divers. Skipper Wilfred Pogto, along with crew members, Bill Anderson and Dick Joliffe, were believed trapped inside the hull. As the hours wore on and air escaped the Unimak those would be rescuers in nearby boats tried desperately to tow the boat ashore. Finally, they watched in horror as she slowly tipped on her beam and sank to the bottom of the ocean.

In August when the salvage crews towed the Unimak into Sechelt, the bodies of Bill Anderson, 28 and Dick Joliffe, 35 were pulled from the wreck. The Skipper Pogto was not found. On a sad note, only the survivor Bob Pederson was entitled to Workers Compensation (WCB) coverage. The paperwork for the others had been submitted but not processed. Bureaucracy trumps death and suffering when it comes to workers.

A Coast Guard rescue service could have saved lives Pederson told the media. “It’s a shame a country this size with so many men going down to the sea, and so many small boats travelling this coast, that they haven’t provided proper rescue service.” he said.

The Fishermen’s union, which had been campaigning for 12 years, hoped for some good from the tragic deaths of four people. “The union members consider the lack of a coast guard a complete disregard by the government of the safety and lives of the men who go down to the sea in ships,” a columnist wrote in the Vancouver Sun. “A coast guard with specially trained firefighters and ships and crew well versed in rescue at sea is essential for protection of our seafarers.”

In a letter to the editor of the paper a Nanaimo citizen wrote, “In the last few years, the federal government has spent hundreds of thousands of dollars on a fleet of launches for the RCMP marine division. Any seaman acquainted with conditions on this coast knows these boats are wholly inadequate for rescue and salvage duties.” He criticized the government with being more concerned with enforcing the Small Vessels Regulations “on rowboats and the odd gillnetter not equipped with Department of Transport-approved (and obsolete) life jackets, etc.” He adds that “the Americans have the best coast guard in the world, and they keep their police forces on shore where they belong.”

Many questions came from the Unimak Coroner’s Inquest. Why didn’t Air Sea Rescue fly the divers to the sinking ship? This would have given them about 3 hours instead of 30 minutes to try and open a jammed sliding door behind which two men died. Why does not the Air Sea Rescue crash boat come equipped with obvious rescue tools, in the same way, for example, as Vancouver’s Safety and Rescue wagon? Who made the mistake in the location? And finally, “Will the government now learn from the Unimak that they are at least four lives too late in establishing a coast guard?”

Vancouver Conservative Member of Parliament Douglas Jung took up the fight of the Fisherman’s Union attending a meeting to put pressure on Transport Minister George Hees to establish a true Coast Guard. (Both Jung and Hees were members of the Diefenbaker government.) The union claimed there had been occasions where government ships have been tied to shore by red tape when a call for help has been put out by a fish boat. “Several times, while government boats were awaiting clearance from Ottawa, the American coast guard has left Washington or Alaska waters to assist a Canadian vessel.”

What happened would shake up the government of John Diefenbaker and the Department of Transport. The second shipping disaster on the west coast drew national attention showing the government that a Canadian Coast guard was needed, and it had to have a Search and Rescue fleet.

The political pressure on the federal government had become too much. On Sept 13th it was announced that Canada was going to get a form of a coast guard service to patrol both coasts and the Great Lakes. It would be named the “Canadian Marine Services.” Transport Minister George Hees said that the service would have six fast new ships between 75 and 125 feet purposely built that will carry trained divers and fire fighters. The service will also combine the facilities of 145 department of transport vessels, private ships and the RCAF Air Sea Rescue organization.

Three marine coordinators would control Air Sea Rescue, guiding both government, and private vessels. All government ships would have to notify the Coordination Centre of their location so that those ships could be used in the event of a distress call. An improved radio system to address blind spots on the west coast and a new weather radar program to improve analysis and forecasting would be established. DOT would provide education for boat owners and crews to aid them in case they are the object of search and rescue. In communities where no government employees were located locals would be trained in emergency procedures and how to get the Canadian rescue service into quick operation.

The newspaper headline following the announcement gave the Fishermen Union’s response “Union wants more, Larger Ships, Use of Five Helicopters in Plan.” The plans look like half measures, even quarter measures the union said. It called for a full-scale judicial inquiry into the July 22 sinking of the fishing boat Unimak with a loss of four lives on the grounds the rescue attempt was “slipshod and disorganized.” The Union wanted a minimum of four cutters on the west coast, it wanted larger ships than proposed, five helicopters, and an immediate start to construction. “All this happened only a short distance out of Vancouver, and with many ships standing by, two men were alive for about six hours and then drowned. The public should know the full facts,” the union’s Secretary Homer Stevens told the media.

Then on January 26, 1962, the Minister of Transport rose in the House of Commons to announce that the from that date forth the DOT “Canadian Marine Services” would be known as the Canadian Coast Guard. The 241 vessels would be painted with the colours red and white replacing the black, white, and yellow they were currently carrying. New uniforms would be issued to the 1,676 members and the civilian character of the service would be maintained. Finally, it was official Canada had a Coast Guard. The seas and Great Lakes are safer thanks to the work of UCTE members.