Just who Was Responsible for Sea Rescues? (Part 2)

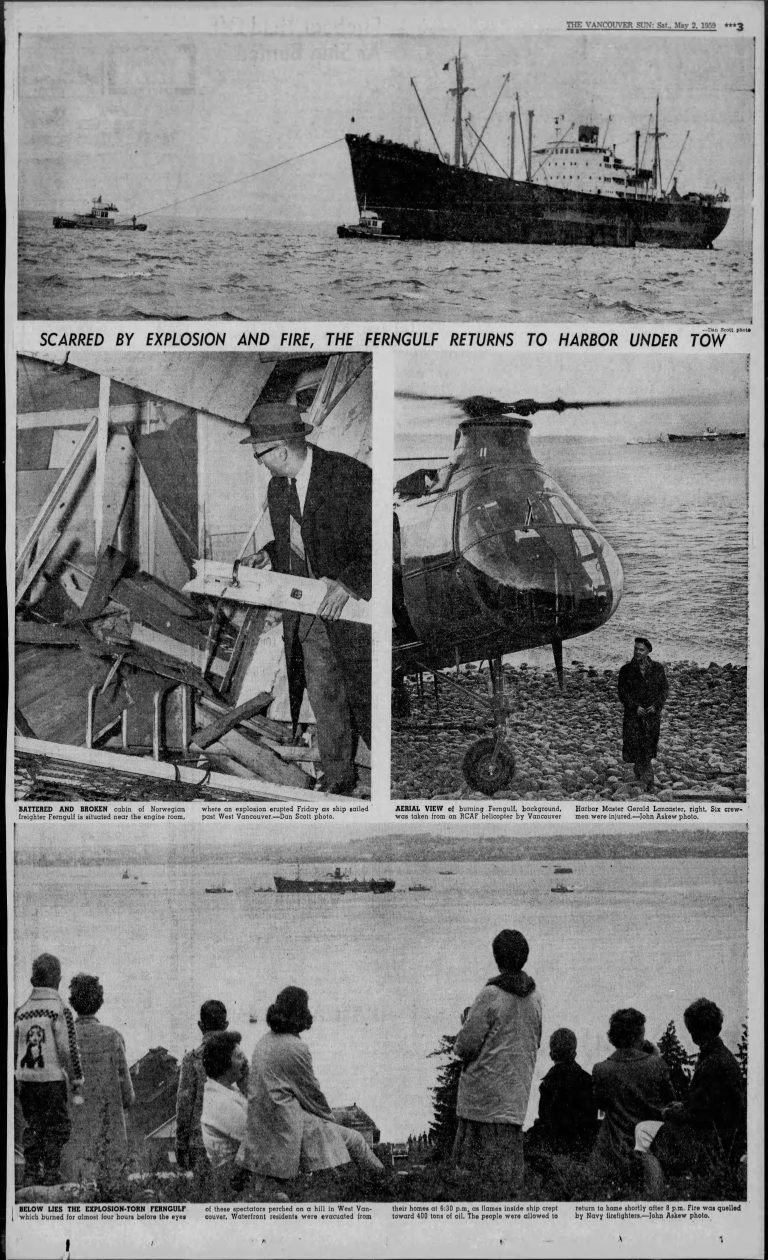

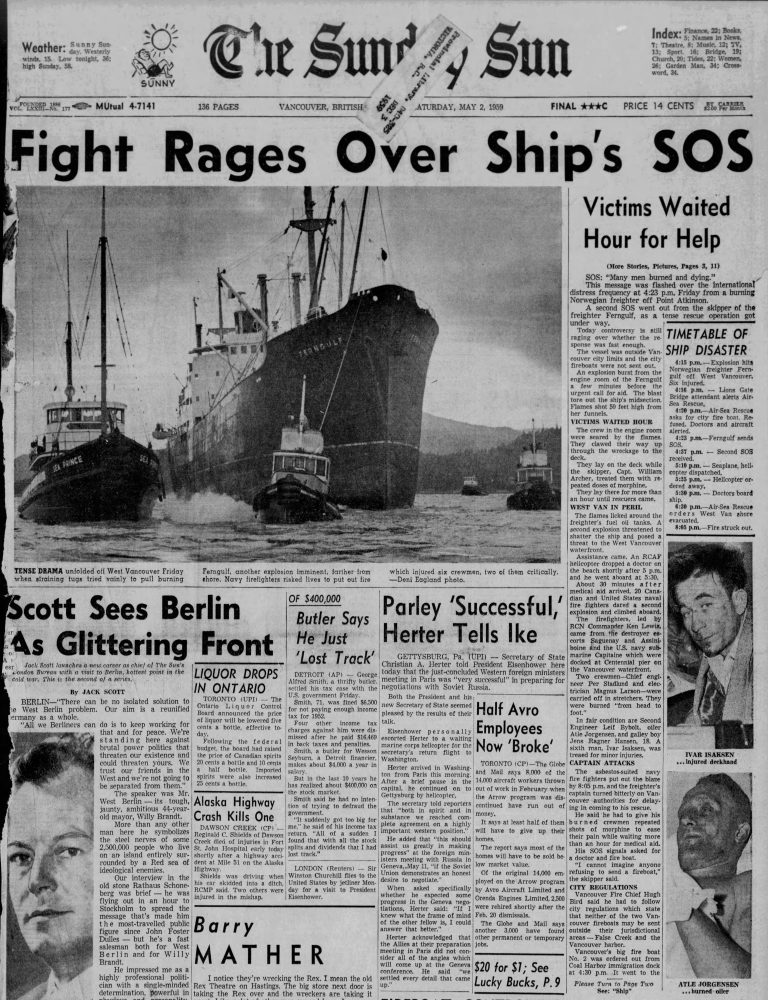

Vancouver Fire Chief Bird told the media that the Ferngulf explosion and fire pointed to the urgent need for a coast guard. The skipper had a “perfect right to be angry,” he said. “But the city fire department can’t be expected to supply a coast service.” He also was trying to deflect criticism from the City of Vancouver. Both the Chief and his deputy, Elmer Sly, protested that the Ferngulf never sent an SOS distress message following the blast. They pointed out that two other freighters passed the vessel after the explosion and did not stop so how were they to know it was an emergency? Department of Transport (DOT) air services pointed out that many ships do not keep their radios tuned to the 500-kilocycle distress frequency while in port so they would not have heard the distress call. Information was both conflicting and scanty. The Chief claimed the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) rescue co-ordination centre which passed on the freighter’s request for a fireboat, did not say it was an SOS. But Point Grey Marine Radio Station and the United States Coast Guard in Seattle reported receiving two SOS messages. Sailors were dying, a ship on fire within sight of the city, an evacuation of residents could be organised but organizations that could help a ship in distress could not coordinate themselves.

As a result of the accident many harbour, civic and rescue officials urgently demanded action by the Federal Government to establish a coast guard in BC. The Seafarers’ International Union, the Marine Workers and Boilermakers’ Union, and the BC Federation of Labour President Bill Black spoke at a meeting of the labour council and called for a Coast Guard. “We cannot condemn the Vancouver fire department for their lack of immediate action. It is actually a problem for the department of transport in Ottawa,” said Black. “It’s a serious situation where a boat lying in harbor flashes an SOS and everyone denies responsibility for at least 1 ½ hours.”

Since the end of the Second World War there had been calls for a Canadian Coast Guard. It was not only unions but virtually every business group and local government that faced the sea or the Great Lakes at one time had made that demand. They told the Federal Government that the diverting of their ships engaged in other work was no answer to a marine distress call. In 1950, two fishing boats off the coast of Nova Scotia sank and no government vessels were available to respond because they were tied up in port. Instead, it was the United States Coast Guard that made a search for survivors. In 1953 the British Columbia government passed a resolution requesting the establishment of a Coast Guard and a Search and Rescue component.

Canadians were very much aware of the US Coast Guard and its reputation. The Seattle Coast Guard reported if the explosion had happened in American waters, it had seven boats with firefighting equipment that would have been on the scene of the Ferngulf in less than 20 minutes. There would have been a Coast Guard fireboat, Seattle fireboats (one of two the city owns), the other 5 were Coast Guard cutters all equipped with minor fire-fighting equipment and specially trained crews that would know how to fight a shipboard fire. In Seattle, it is the Coast Guard duty officer who evaluates the emergency and has the power to order emergency equipment to the scene. “If the disaster was within reasonable distance from the city – within 10 miles – one of the city fireboats would respond to our call,” they told the media. “If it was an SOS, they would be obliged to respond.” Clearly Canada was not in the same league.

There were two Fireboats in Vancouver but since one had been funded year’s before by local industries that sat on the banks of False Creek, it was not permitted to leave the area. The fact that most of those businesses had long ago departed did not change the conditions placed on the fireboat in the minds of the city fire department.

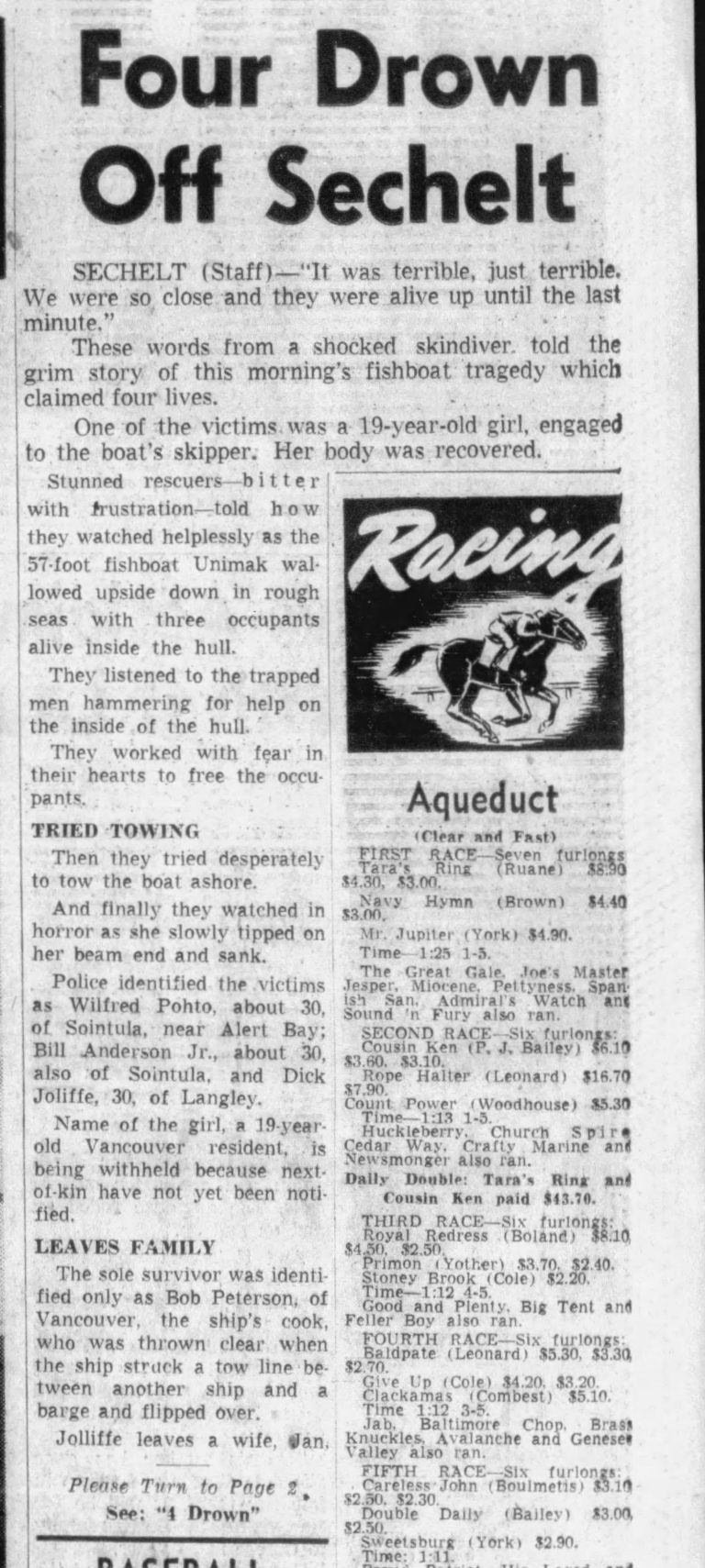

On May 6, 1959, the Vancouver Sun newspaper headline read, “Death Tug Mishap Same as ‘Sisters.’ Six days after the Ferngulf explosion, a tug working in False Creek capsized and was completely under water within seconds. The 28-year-old skipper of the “Navy Jack,” Karl Willy Gursli, died. It was the 3rd sister tug to capsize in an almost identical fashion. Working on the sea, even in a harbour, was dangerous and in the case of a tragedy sailors were mostly on their own.

When the coroner’s inquest met, the Pilot assigned to the ship, told the inquiry that it “was 100 per cent within the Vancouver harbor.” When the jury reported its findings, it attached no blame but urged for a better system to respond to incidents like what happened in the case of the Ferngulf.

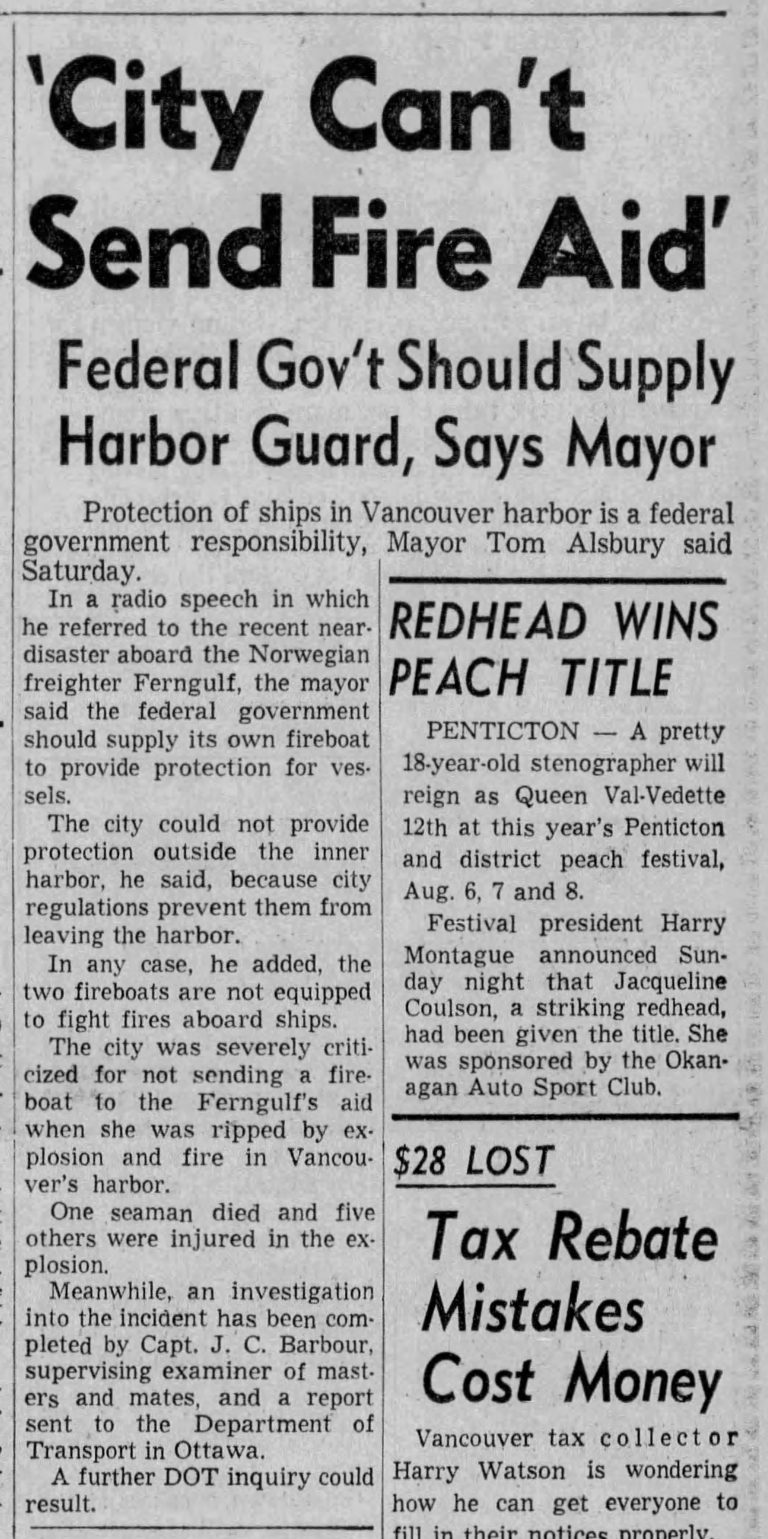

While the inquest found no blame towards the City of Vancouver, it was still feeling pressure for its role that fateful day. “Protection of ships in Vancouver harbor is a federal government responsibility,” said Mayor Tom Alsbury. Vancouver City Council voted to call on government, municipalities, and industries for a concerted action. The position of the city was its two city fireboats were not equipped to fight fires aboard ships. It called on the harbour board to contribute heavily if not entirely to a new fire boat. The city’s position was that even if their fire boat was able to respond, it is not the best way to evacuate injured seamen. This required trained search and rescue crews.

As spring turned to summer members of the lady’s auxiliary to the National Association of Marine Engineers started a fundraising campaign for the families of the Ferngulf’s crew. They were joined by other marine unions: the International Longshoremen’s and Warehouseman’s Union, the Burrard Drydock, the Marine Workers and Boilermakers Union and the Canadian Brotherhood of Railway Transport and General Workers. Workers would attempt to care for the families of the dead sailors.

By the fall of ’59 the Federal government responded to the building pressure. The Minister of the Department of Transport announced the creation of what was to be called “Canadian Coastal Marine Service” of the DOT. Marine search and rescue co-ordinators were to be appointed in several regions. The Vancouver Sun headline spoke for many when it read It Still Isn’t a Coast Guard. The papers Editorial proclaimed, “What makes a coast guard is the ships, and the men properly trained to man them.” The editorial ended with these words; “The bureaucrats have been wrong for a long time about the need for a coast guard. If they’re reluctant to admit it by using the correct title, it’s something we can allow them. Providing they’ve really seen the light.”